The success of Fury, the new World War II movie starring Brad Pitt that was #1 at the box office last weekend, could mark the start of a new trend in how Hollywood depicts war. In the years after 9/11, our movies reflected all the complexities of the War on Terror, from its morally ambiguous tactics (Rendition) to the new realities of combat (The Hurt Locker) to our cultural obsession with revenge (Zero Dark Thirty). The release of three WWII movies this Oscar season – the others are The Imitation Game, on the life of codebreaker Alan Turing, and Unbroken, Angelina Jolie’s epic on American POW Louis Zamperini – may signal a shift in American thinking on foreign conflict. Perhaps, after more than a decade of dealing with an ambiguous war and its dreary cinematic portrayals, American audiences are thirsting for a simpler form of patriotism, and are eager for a conflict – and a film – in which they know unequivocally who to root for.

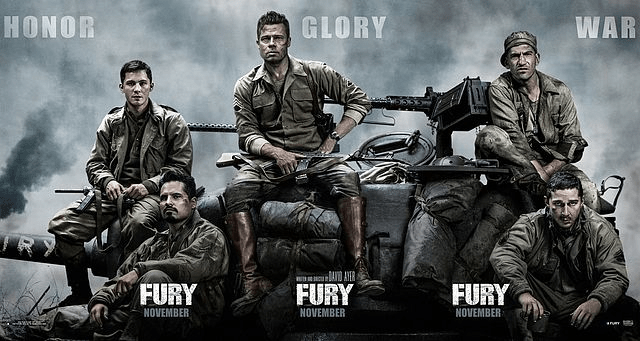

World War II certainly satisfies these demands, but there are worrisome signs in Fury’s approach, which combines Saving Private Ryan-style realism with the narrow patriotism of last year’s Lone Survivor. Its ostensible subjects are the gruesome realities and opportunities for heroism that the military provides, but writer/director David Ayer frames the story as a celebration of war – even of killing itself – not a resigned acceptance of its necessity. He achieves this by setting the film’s events in the final days of the war, when the conflict is nearing an end but, as one character puts it, “a whole lotta people gotta die.” Ayer, for one, seems giddy about this reality, and he revels in the Tarantino-esque levels of violence without injecting any of the Inglourious Basterds director’s subversive wit and stylized aesthetic. The opening scene finds Brad Pitt leaping off of a tank to stab a Nazi officer in the eye, and the violence escalates from there in punishing ways.

Of course, war is violent. Fury is no more bloody than Saving Private Ryan, but the violence here serves a different, more disturbing purpose. You can trace the values of the film in the journey of the one character who undergoes a transformation: a young, inexperienced Army typist named Norman (Logan Lerman) who joins the tank squadron led by Don “Wardaddy” Collier (Pitt). Collier and his crew are already hardened to the realities of war, which Norman experiences the first time he cleans out the inside of the tank and discovers a soldier’s face – removed from its head. This moment marks the beginning of The Desensitization of Norman, a process by which the young innocent slowly sheds his naïve, peaceful ways and learns to relish mowing down the faceless, nameless Nazis in the tank’s path. By the film’s climax, in which he kills dozens of enemy soldiers while shouting obscenities from inside his tank, he has truly earned his dehumanized war nickname: Machine.

Since Nazis are a universally-accepted symbol of evil, why shouldn’t we celebrate our victory over them? For starters, even the most hawkish among us would acknowledge a moral difference between celebrating a military victory and reveling in the bloodshed and murder of our enemies. Further, depicting Nazis as faceless monsters may be emotionally satisfying, but it is also a disturbing cultural regression, given the efforts of many authors and thinkers after World War II to show them as complex, misguided human beings.

In 1963, Hannah Arendt published Eichmann in Jersualem: The Banality of Evil, in which she painted a portrait of Nazis as “thoughtless” and “terrifyingly normal.” Reporting on Eichmann’s trial for war crimes, she wrote that: “[E]verybody could see that this man was not a ‘monster,’” but the public did not welcome this interpretation. Arendt received death threats for her portrayal, but her views increasingly took hold. Her take on Eichmann was emblematic of the characterizations of some of the other Nazis tried at Nuremberg. They were not cartoon villains, as many had anticipated or hoped. Some were simply well-meaning individuals – good fathers and animal lovers – who had given themselves over to an ideology and lost empathy for those they persecuted. They committed unspeakable acts, but this did not necessarily make all of them monsters. “If only it were all so simple!” wrote Nobel Prize winner Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in The Gulag Archipelago 1918-1956. “If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.”

Fury forgets this aspect of the human heart, or is uninterested in knowing it, and it turns a story of American bravery and fortitude into something that more closely resembles war propaganda. The film is so focused on depicting the horrors of war for American soldiers that it fails to see the enemy as even human. Early in the film, Collier forces Norman to kill an unarmed Nazi soldier, as part of his desensitization training. Norman resists, and Collier literally forces his hand. When he finally complies and shoots the prisoner of war in the back, we are only asked to feel bad for Norman and Collier for being driven to such brutality. There is not a moment of sympathy or dignity for the German soldier whose life they have just ended. In other words, the horrors of war only extend to the soldiers on our side.

While it is unlikely that the other WWII films being released this fall will follow Fury’s blood-soaked path, the fact that Hollywood is focusing on such an uncontroversial war at all is telling. Why now? There is no anniversary of a major WWII milestone this fall. Perhaps Hollywood thinks the American public is looking for simple war stories right now, and if so, Fury may not be about Nazis at all. My high school history teacher always told us to be skeptical of our textbooks because they tell you as much about the time they were written as they do about the history they present. This probably goes double for historical films, which by definition de-prioritize the pursuit of historical facts in favor of drama (especially with Fury, which is not even based on a true story).

For example: It is telling how the values of Fury line up so nicely with Americans’ sentiments towards our current global enemy: ISIS and other radical Islamists. For much of the last decade, Americans were wary of further involvement in the Middle East, and the glut of anti-war films in the post-9/11 decade reflected that. But after witnessing the recent beheadings of two Western journalists, the public now supports an American war on ISIS (it is a gruesome coincidence that Fury’s violent image of choice is of a head exploding after being struck by a bullet).

While Ayer could certainly not have predicted these developments, it is equally clear that he intended Fury to be a comment on contemporary global affairs. “Ideals are peaceful,” says Pitt’s character in one of his many lessons to Norman, “but history is violent.” It is odd to hear a character use the term “history” to describe his current actions, but this phrasing betrays Fury’s real purpose. It is not about World War II. It’s about justifying modern-day military conflict through historical paradigms. It’s about using the nomenclature of a simple, morally unambiguous conflict to rally support for one that deserves a little more scrutiny.

Brutally violent films, however, do not lend themselves to scrutiny. If anything, they leave the viewer in a state of shock, perhaps feeling a small fraction of what actual soldiers experience. And this rarely leads to greater understanding of the real issues of war. Martin Luther King once said, “Violence as a way of achieving racial justice is both impractical and immoral. It leaves society in monologue rather than dialogue.” A powerful voice in the anti-war movement, King would surely have extended this idea to other forms of justice. Bearing this in mind, we can view Fury as an effective depiction of the horrors of war, but one that is unlikely to start any meaningful conversations.

The Nazis suffered the bad luck of being on the losing side. Those who were executed at Nuremburg were executed not for what they did, but because they were on the side that lost.

“Some were simply well-meaning individuals – good fathers and animal lovers – who had given themselves over to an ideology and lost empathy for those they persecuted”.

Hmmm….that could EASILY describe war criminals like Dick Cheney, George W. Bush, Donald Rumsfeld, Barack H. Obama, the list goes on and on…..

But since those aforementioned psychopathic scumbags are still in a position of power they are not facing the gallows, but they are no less deserving of the same fate as any convicted Nazi.